Directing Plays with Magic Systems: Making a Fireball about Character Development

As a huge fan of fantasy stories and love to develop or direct a story about wizards, magic, and fantastical creatures for the stage.

Typically, these stories involve magic as a key storytelling component. Magic systems in theatre ask the artists to solve problems in different ways that we are used to seeing visually executed with CGI on the screen or with our imagination when reading a book about our favorite dragon slayer.

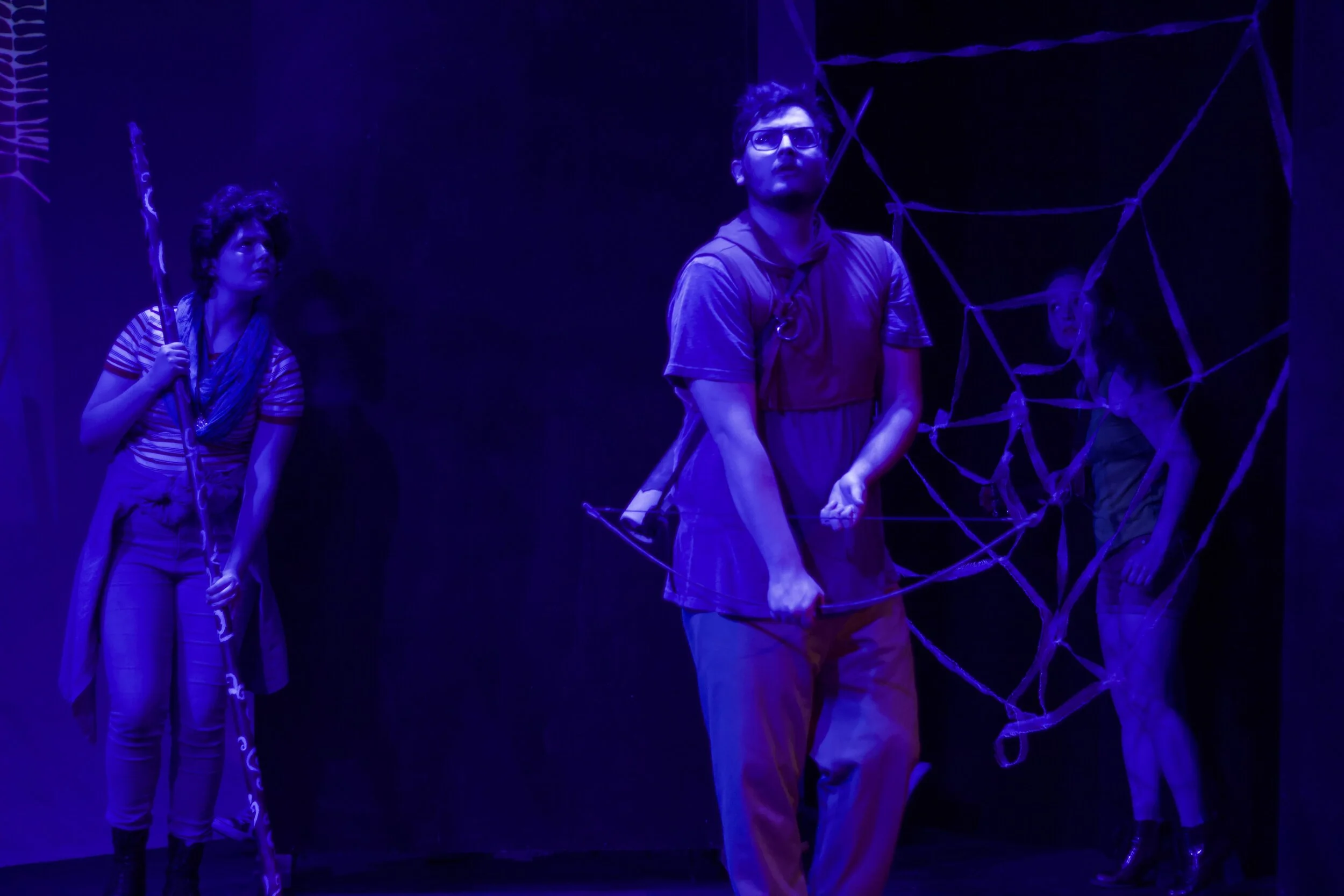

For the 2018 Hollywood Fringe Festival I directed the new play Survival Check by Amanda Lloyd. This story follows a band of friends who go on a camping trip to cope with the death of a loved one and find themselves in a Dungeons & Dragons world. Through swinging swords and slinging spells, the party levels up and slays demons in this fantasy world and the ones they personally hold.

When working with actors and the design team on creating a world with a magic system, or developing rules around how the magic works in the storytelling and how the magic is physically executed on stage, I reference Brandon Sanderson’s Laws of Magic.

Sanderson’s three laws were originally created for writers to craft and better specify their own magical world. I find that the same principles can apply to directing a play and can help lift the human connection in the magic the writer gives us.

An author’s ability to solve conflict with magic is directly proportional to how well the reader understands said magic.

Sanderson’s First Law

The building blocks of theatre are the series of actions the character pursues to get what they want. Magic in the story is a tool for the character to accomplish their action.

If it is scripted that a character kills another. One doesn’t just fall to the ground. Hamlet needs to stab Laertes. Hamlet needs to poison the king. Hamlet needs a tool to accomplish his action. Magic is the same. The audience understands the rules of how stabbing works. You take a sword and you stick it through your foe.

But walking into a play with magic, the audience may not have a baseline rooted in real life of how spells, potions, or other supernatural elements work. The audience will need to be shown the rules in this particular play of how magic works on stage and how the characters use it.

Magic is a tool for characters to use to solve problems and conflicts. How they use it and what it looks like is the creative work of the artists involved.

When the audience understands the magic system it makes it feel like the character’s experience, intelligence, and ingenuity allows them to solve problems. The audience should care about the character’s pursuit of the action more than the magic effect; just as the audience cares more about Hamlet’s desire to the right the wrongs of his late father more than the sword he uses to stab Laertes.

Magic should not just solve problems. Magic should be the tool of the character’s choices to solve problems.

In rehearsal, I worked with the staff-wielding, spellcasting Andy in Survival Check (played by Nicoletta Brunelli) and the fight choreographer (Lauren Gaudite) when a new spell was introduced and what the audience knew about that spell. We then paired that knowledge of the audience’s understanding of the magic system with what Andy wanted to accomplish in that moment. From there, we discussed the style casting the spell and what the visual execution should look like.

Never at any point do we want to rob the character of their agency, intelligence, and experience by having the magic solve the problem for them. The amount of spells Andy knows and the level to which Andy understands the spells determines what magical tools Andy can use to accomplish her actions.

Limits are more important than powers.

Sanderson’s Second Law

If the character’s action is too easy to accomplish then there is no conflict. If there is no conflict, there is no story. Every action pursued needs an obstacle to fight against to create richer and more vibrant storytelling.

Hamlet wants to poison the king, but maybe the cup is on the other side of the stage or there are too many people watching.

How the actor deals with that obstacle to pursue the action reveals more about the character. Hamet can hide behind a series of curtains to make his way across the stage unnoticed. He can smooth talk, using his charm and wit to distract others while he poisons the cup.

In having to manage the obstacle, the audience has learned more about how Hamlet solves problems. Additionally, the scene has become more engaging than Hamlet casually walking up and poisoning the cup.

Actions need obstacles. Magical actions need magical obstacles.

When encountering a new magical element in the play, work with the actors and design team about what are the limitations around that element and what obstacles come from those limitations.

Do they need to be holding an object for the magic to work? Does the magic work only work at a certain range? Does the user become tired after using a spell? Limits create conflicts and force creativity from your characters to solve problems.

There’s a scripted moment in Survival Check where spellcaster Andy needs to shoot lightning at an enemy. Andy can hurl a lightning blast and move on to the next action, but then there is no obstacle. And as a result, we miss an opportunity for the audience to learn more about how Andy solves problems.

Nicoletta and Lauren experimented with options in rehearsal, and loved the idea that the lighting spell exhausts the user. An idea that came from discussing what Andy values and what would be the worst possible situation for her in a battle.

Now Andy’s action has been upgraded from defeat the enemy to protect her friends. The obstacle of using the lighting spell as a tool to successfully protect her friends is the knowledge that it will put herself in danger.

Andy now has the agency of choice. In having to deal with the obstacle, the audience now knows that Andy values the lives of her friends more than her own.

Finding limits to your magic system will naturally create opportunities for increased conflict and character development.

Expand what you already have before you add something new.

Sanderson’s Third Law

The audience’s investment in the storytelling comes from how much they care about the characters. Audiences want to root for someone and, ultimately, see themselves in the people onstage.

When we introduce magic into the story, we by nature have something that the audience cannot relate to. They will not fully understand what it is like to wield lightning or use music to control emotions.

They will understand the desire to use whatever is at their disposal to get what they want. They will understand the character’s relationships that make them want to use that power to defend what is theirs.

When dealing with magic systems, we have to focus on predictable rules to show concise growth of new powers or we run the risk of the audience no longer connecting with the characters. A new lightning spell may be flashy and visually fun to make onstage, but if the new spell is not earned through the development of the character, we then remove the audience from sharing in the growth of the people they have come to know.

Tying the magic system to character growth gives more weight to the character arc by emphasizing its importance in them becoming stronger and overcoming challenges. It also places magical prowess secondary to character growth. Work with the actor and design team how the magic follows the same path they take as a person. They should feel one in the same.

Survival Check ends with spellcaster Andy using a fireball spell to ultimately defeat the big bad. Narratively, the fireball spell became the most important link between Andy’s character growth and how the audience understood the rules of magic.

At the beginning, the fireball spell happens by accident, she cannot control it, and is afraid of it. After Andy goes through the emotional transformation of trusting her abilities and proving to herself that she can take control over her own thoughts and actions, only then can she wield the fireball at will.

Visually executed, the first fireball spell we see is wild and untrusting and the last one we see is precise and determined. The development of fireball spell is related to the development of Andy as a person.

Had we introduced a new spell for Andy to beat the big bad that the audience never saw then we lose the emotional investment. She gained that ability offstage and the audience did not share that moment with her. The viewer may feel that they are separated from Andy’s character growth and her magic is now a gimmick to solve problems.

Cool people mentioned:

Sanderson’s Laws of Magic | Hollywood Fringe Festival | Gallery - Survival Check | Nicoletta Brunelli | Lauren Gaudite | Amanda Lloyd